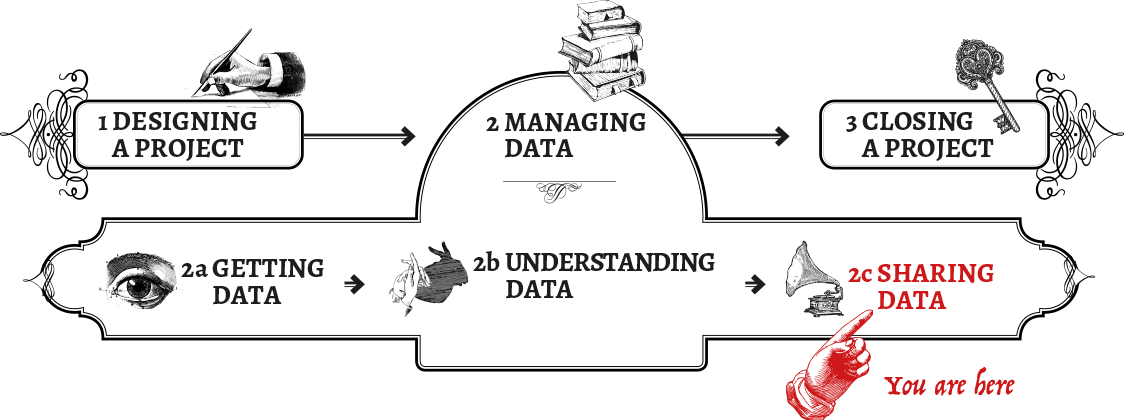

Sharing Data

what to do with your processed data

When to share, when to publish

Once data is collected, it can be released in a variety of ways, from closed networks within an organisation, to platform-dependent sharing between peer organisations, to publishing with closed licenses, to publishing with fully open licenses. It’s often tempting to think that making data available to the widest possible audience is the best way to maximize that data’s impact.

This approach can also be motivated by the desire to do justice to all the hard work put into collecting, cleaning, verifying and analysing. However, it’s worth carefully considering the various forms that sharing can take.

Models for sharing can differ both qualitatively and quantitatively, and there are various levels of sharing that you can adopt. Sharing may be an optional or a mandatory activity, depending on the source of funding or sponsorship, the nature of the organization, the type of data involved and other factors. It can include information about the original exercise and purpose for which the data was collected, but can always be repurposed by others, sometimes for purposes contrary to the project that first shares.

Benefits and limitations of sharing

There are many obvious benefits to sharing data. Doing so can maximize the impact of data (or conclusions drawn from it), inform collaboration, provide stronger evidence for advocacy, increase efficiency of service delivery among a wider audience than just within your project, or play a role in decision making within other projects, to name just a few potential benefits.

Publishing your data can also allow people who might not have otherwise been well-informed enough about your project, to have a say - for example, those who are reflected in the data. Without the data being made ‘open’ and accessible to them, their information channels about what is happening in their communities might be severely limited: put otherwise, providing them with proactive access to information is a crucial step towards empowering them to make their opinions known.

Sharing, in the sense of publishing open data, is also an increasing trend. The open data and open government movements, as part of pushes for better transparency and accountability, as well as recent interest in shared measurement for project evaluation, are just some examples of how the international norm for sharing data has gained powerful traction in recent years.

Sharing can also have unintended consequences, however. Once data is published, it’s impossible to anticipate how it might be shared further, and once it’s out in the open, there’s no telling how it will be adopted, re-purposed and re-used for any number of purposes. These might be positive purposes, finding uses for your data that you had never imagined yourself. But, some of these purposes might be malicious or run counter to your project’s strategic objectives, and others might call into question the premises on which your project work was conducted. Still others might expose your data to new audiences and new risks.

Given our inability to see into the future, it’s especially important to think carefully about what kind of data gets shared, and the relationships, licenses and agreements that govern limited sharing. Apart from the ethical implications of unforeseen use by others, there may be practical considerations: for example, participants seeing that their data is used in a way they don’t agree with, or that puts them in danger, might mean that they refuse to participate in subsequent research or development efforts, either with you or with other data-intensive projects generally. As you can imagine, this has much wider societal consequences, and deserves careful thought and work to avoid such a situation.

Sometimes, technical measures to strip identifiers, redact sensitive information or otherwise “anonymise” data may be sufficient to mitigate against such potential harm. De-identification is problematic, however, andrarely works as a magic bullet.[ For a thorough discussion on this, see the section about Anonymising Data.]

The bottom line here is that you should carefully consider the implications of sharing (from the point of view of the people to whom the data relates, as well as the bigger picture), whether to share at all, and the licensing conditions or terms and tools that you can use to reduce the risk of harm, while still permitting beneficial outcomes.

Whose data is it anyway?

Many will argue that data should belong to the people who have provided it through reporting, answering surveys or simply by using devices and media that generate a data trail. This implies that data subjects have a right to be informed and consulted about how their data is used, and to require that their explicit consent be obtained for specified purposes and be refreshed for each new purpose beyond the scope of the original consent. However, this norm is difficult to operationalise in many situations: for example, among communities with low levels of data literacy, or in particularly rural and hard to reach areas.

Others argue that data subjects have rights associated with the result of analyses conducted on the data, in addition to those associated with the raw data itself. These sorts of secondary data rights may suggest entirely different ways of engaging with data subjects and participants, and the ways in which consent is operationalised.

It will inevitably be up to individual projects to determine what kinds of data rights are appropriate in specific instances. It will be important that these decisions are made explicit when data is shared or published, and that appropriate licenses or agreements are applied. (See chapter: Power to the People)

Legal and contractual frameworks

Legal systems often include some version of a purpose limitation principle, in which data collected for one purpose cannot be used for any other purpose without the consent of the data subject. This is often seen as a way of respecting boundaries and choices.

Data sharing can often challenge this foundational principle. If, at the data collection stage, another common principle of data minimisation (collect no more than you need for that specified purpose) was also ignored, this problem is compounded. Having collected too much data is problematic, but potentially unproblematic, as long as the data is kept in-house. This is another reason you need to think carefully before you publish or share more widely however. See section Sharing Data.

For sharing data with a limited set of actors, it is worth considering whether data sharing should be governed by explicit agreements such as MoUs, or even contracts. Agreements are imperfect solutions insofar as enforcing them is rarely simple, and any breach means that the data is already out of the bag, but they also have some advantages. Entering into agreements about the conditions, limitations and ethical guidelines that govern data sharing can impose some measure of control, and can also establish a shared set of expectations and reveal previously unforeseen risks. Highly explicit agreements about risk and responsibility can also be shared further down the chain of actors with whom data might be shared and reinforce awareness about a responsible data approach among actors not directly within your project’s sphere of influence.

Sharing Data

After considering the points in the previous chapter, you may have come to the conclusion that your data can be responsibly released into the wild, at some level. The next sections are designed to help you think about the different groups you can share with, and the appropriate checks and balances you should consider for each level of dissemination.

Sharing internally (within your organisation)

Perhaps the data that you have collected will be of particular interest to your colleagues, who might be working on similar issues, or within the same country or region. This is a relatively restricted level of sharing - just within your own organisation, department or formally organised consortia or partners.

Be aware of the blind spots that internal sharing often entails: you are probably seeking feedback from like-minded individuals who know where you’re coming from, understand the issues you’re dealing with, and know what to look for. They will be able to provide you with vital feedback, validation of assumptions, and will understand the importance of keeping the data safe and secure in this very sensitive first phase. But they will likely be sharing your own biases and won’t be able provide truly independent feedback.

The wider you go within your organisation (or consortium/partnership), the more diverse feedback will be, bringing with it truly fresh perspectives come in. However, the wider you go, the less control you have. An important aspect of this level of sharing is the presence of an organisational security policy: a set of rules and guidelines providing you with a framework that you can safely assume your colleagues, partners or co-workers, will follow when dealing with the data. See section Data consent, for your eyes only….

TOOLS:

Collaborative tools, private Github repos, etc

Controlled closed sharing

Another sharing option might be to share the data with people outside of your own organisation, but to retain some level of control. It’s worth bearing in mind that for most NGOs, this almost always has to be a smaller and tighter data set than what can be shared in the earlier stage: this will be easier if you have already had input from those fresh perspectives we mentioned above.

For example, the data could be shared with peers for external opinion, or even data aggregation, in case they are working on similar themes (beware of combining apples and pears when combining different data sets, however).

Data aggregation is a crucial point of risk assessment: sometimes standalone data deemed safe becomes harmful when combined with other data sets, or data that you thought was anonymised becomes easily discernible once combined with other data, using triangulation techniques. (see section: anonymising data) Another reason for sharing externally is the advantage of getting different expertise. Sharing data with other organisations can help to recognise the gaps in your data set, making for a more resilient and more trustworthy data set. It is all too easy to unknowingly apply your own personal biases when collecting data (for example, within questions asked in surveys, or structuring of the data), and sharing it with people who weren’t involved in early stages might help to identify these biases.

One last aspect to mention here is the sanity check: sharing your data with unusual suspects will provide you with opinions that are outside of the echo chamber you are used to, and can help to expand the dimensions of your project. You could, for example, share the data back with the people reflected in the data, and see what they think of what it reveals. Often, doing this is a responsible thing to do anyway.

When connecting with external organisations, it might be useful (or sometimes, organisationally mandated) to put in place legal constraints of how your data will be used. Tools like a non-disclosure agreement can provide legal leverage for ensuring your data is not misused, or that it is treated safely, and doesn’t get shared any wider than you are envisioning.

When collaborating using the same tools, software will often allow you to configure access permissions or check logs for suspicious activity. This will not help you prevent leakage, but will help you identify any proactively, which will in turn allow you to take measures for containing damage.

TOOLS:

Non-disclosure agreements, Memorandum of Understanding, collaborative software

The point of no return

So you want to publish your data - at this point, you’re most likely talking about a smaller, more controlled portion of your data, which you have carefully checked for any weak points, sensitive points, inaccuracies, and biases.

Once the data set is shared publicly, the proverbial cat is out of the bag. Any weak point in the information, any personally identifiable information that hasn’t been properly addressed, will be impossible to mitigate because someone might have already made a copy. The sections above offer a strong validation and checkup process; however, a final risk assessment of the data is more than warranted.

If you’re at this point, your data set has likely changed since the very first version you might have been working with, and is hopefully more robust and secure now, it might also be that some aspects have slipped through the cracks.

There’s another group that need to get back to at this point: the people who are reflected in the data, or the data subjects. Before publishing information that, however unlikely, might put individuals at risk of harm, you should set up procedures to connect either directly with the involved people, or with representatives of communities you are collecting data from, to get their final go-ahead before data is published.

If you are confident that the data is ready for sharing with the world, please proceed to the next chapter: publishing data.

TOOLS: Risk mapping tool in development, from the engine room

Publishing Data

So you want to publish your data - here we’ll take a look at various options for formats, platforms to use, licensing and whether or not to make the data ‘open’.

Open vs Closed

You might have heard of the buzz around ‘open data’ - but what does this actually mean?

According to the Open Definition: open data can be freely used, modified, and shared by anyone for any purpose

This means that published data, or online data is not necessarily open data. For example - data that is published as an Excel table within a PDF document, without an open license (more on this below) - is not open data, because it can’t be easily managed or re-used. Whether or not you want to ‘open’ your data is an important consideration.

There are many benefits to open data:

-

It can be easily re-used and re-purposed for complementary development and social good activities, saving resources and avoiding duplication.

-

It can be a means of building capacities and standards for evidence among development and non-profit organizations.

-

It encourages transparency and encourages accountability to participants, beneficiaries, peers and data subjects.

-

It can be verified and quality controlled by a larger group of interested parties.

-

It can also be easily combined with other datasets to address longstanding problems, and reveal patterns that might not have been obvious in isolated data sets.

However, making data ‘open’ also allows potentially malicious actors to use the data for their purposes: this is really important to bear in mind. As the saying goes - the best thing to do with your data will be thought of by someone else… but this also means that, potentially, the worst thing to do with your data will also be thought of by someone else.

CASE STUDY: School attendance

In Country X, there was a region where, in certain schools, the school attendance of girls aged between 12-15 was unexpectedly low. The Ministry of Education ran advocacy and information campaigns to families, trying to highlight the importance of girls’ education - but there was no change. The problem was only solved when open data sets from the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health were combined: it turned out that all of the schools that didn’t have proper sanitary facilities were experiencing the drop in girl’s attendance. When the girls started menstruation, they had to stay at home, and this led to a big drop off in their attendance after they had missed so much school so regularly. The Ministry of Health installed proper sanitary facilities in the schools, and the girl’s attendance returned to normal levels.

Licensing

Regardless of whether you choose to make your data ‘open’ or not, there are a number of different licenses that you can use for your data. Some aren’t included within the Open Definition, because they specify what kinds of activities (eg. for commercial purposes) the data can be used for, and according to the Open Definition anyone should be able to do whatever they like with the data.

It’s important to think about licensing for a number of reasons: firstly, if you don’t license your data properly, others won’t know if or how they can use it in their work, so they might either have to get in contact with you to check first, or they might simply decide not to use it. If you’ve decided to put the data online to help others in their work, this would be a shame!

Secondly, licensing makes it clear how you want your data to be used. You might want to retain rights to attribution of it, or simply let people do whatever they want with it. If you choose to retain attribution, it makes it easier for you to see how your data has been used by other parties - this can be interesting to demonstrate the impact of the data that you collected (for example, has it been used to support other development efforts?) - or to identify uses of it that you might not have thought of. Keeping tabs on your data also means you are maintaining some level of accountability to the data owners.

Types of licenses

Broadly speaking, there are two main fields of license you can choose from: Creative Commons Licenses, and the Open Data Commons licenses. Creative Commons Licenses are more commonly used for content rather than raw data - for example, photos, text, reports. They have a nice online ‘License Chooser’ which will help you pick the right one for you. The Open Data Commons licenses were specifically created for databases, so might be more relevant here. There are two basic options: Public Domain Dedication License, or PDDL, which puts all of your material in the public domain (ie. for anyone to use), or the Share-Alike (plus Attribution) option, the Open Database License (ODbL).

Here’s a set of Frequently Asked Questions about the Open Data Commons licenses and here is some more information on Open Data Licensing.

Publishing to the IATI standard

The International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) represents a tremendous push for open and transparent data in the international development sector. Initially created as a process through which donors and partner governments could publish their aid flow data, it has quickly become a data standard through which a number of organisations (donors, large and small NGOs, recipient countries and governments) can put their data online in an interoperable way. (More about IATI here.)

There are a number of reasons that organisations should be enthusiastic about publishing to IATI. It’s an important moment for transparency and accountability, and an opportunity to strengthen organisation’s data practices. There are risks to consider as well, however.

Recently, there has been a push for traceability and increased granularity within geocoded data - ie, more detail on where exactly projects are taking place. This would, in theory, allow for more people to keep a closer eye on where exactly money is being spent - is it going where it is saying it is going? But pushing for more granular geocoded data might, in some cases, require a risk assessment first. For example, if an NGO in a country is doing projects that are seen as ‘troublemaking’ by the government in power at the time, providing them (or anyone) with details on where exactly the projects are taking place might put project implementers in danger.

CASE STUDY

In an effort to increase transparency and reduce corruption, the government of a small African country is thinking about making it mandatory for all NGOs working in the country to publish to IATI. This would include project documents, details of financial budgeting and spending, and potentially geocoded data of where project activities are taking place, too. By employing a ‘publish by default’ strategy, they want to show to international donors that they are truly committed to rooting out financial corruption in the country. However, the government also has some restrictive human rights policies in place - and also has a history of political instability, meaning that those in positions of power change frequently. Activities that are deemed ‘suitable’ by NGOs within this political climate could change suddenly, leaving those NGOs and their constituents in danger by publishing their activities to IATI. The government uses the argument that organisations can ask for exemptions if they don’t feel comfortable publishing their activities, but in many of these cases, asking for an exemption not to publish might be interpreted as a signal to government that they are engaging in “unlawful” activities. So here, publish by default has some hidden, potentially dangerous consequences.

While increasing transparency and encouraging accountability around aid activities is clearly a good move, it is crucial to bear in mind the potential risks and outlying cases through which publishing to IATI might put people in danger. The IATI community is made up of people who have vast amounts of knowledge about the data produced and used by global development organisations across the world - if you have a person tasked with publishing your organisation’s data to IATI in your organisation, it might be worth sitting down with them to discuss exactly what is being published, and what is not.

TOOLS: Document Cloud, AidStream, Github, Google Docs, CKAN, HURIDOCS

Anonymising data

Data can have real consequences for real people, and often these consequences are as unintended as they are harmful. This is regularly the case when Personally Identifiable Information (PII) is published, or when seemingly innocuous data is mashed and collated with other data sets. This is why it is very important to try and anonymise information before publishing in any way at all. However, there are many cases where efforts to anonymise have also failed.

At the end of the day, there might be no such thing as perfect anonymisation. Removing all personally identifiable information from a data set isn’t necessarily enough to protect identities in that data set. With the increasing sophistication of analytical techniques and algorithms, “de-identified” data sets can be combined with other supposedly anonymous data to re-identify individuals and the data associated with them. This phenomenon, known as the Mosaic Effect, is particularly challenging because evaluating the risk of it occurring requires one to anticipate all the different types of data that exist or may be produced, and which could be combined with that data set, which simply isn’t possible.

As such, this chapter will talk about strategies for de-identification, because that word doesn’t have the “magic bullet” feeling that is often associated with anonymisation, and because the word itself implies that it can be undone.

It’s also important to underscore that de-identification is a complicated and imperfect science. This chapter aims to help you navigate different techniques, but be careful: Don’t take decisions on publishing lightly, seek expert advice, and err on the side of caution.

Once the data is published, there is no turning back.

What data should be de-identified?

The short answer is, any and all data that has any potential to identify a person. But it is still important to conduct a thorough risk assessment of the possible consequences of data release during project design and update it before release. Once the data is out, it’s too late. Consider the following:

-

Can an individual be identified from the data, or, from the data and other relatively accessible information?

-

Does the data ‘relate to’ the identifiable individual, whether in personal or family life, business or profession?

-

Is the data ‘obviously about’ a particular individual?

-

Is the data ‘linked to’ an individual so that it provides particular information about them?

-

Is the data used, or is it to be used, to inform or influence actions or decisions affecting an identifiable individual?

-

Does the data have any biographical significance in relation to the individual?

-

Does the data focus or concentrate on the individual as its central theme rather than on some object, transaction or event?

-

Does the data impact or have the potential to impact on an individual, whether in a personal, family, business or professional capacity?

If the answer is “yes” or even “maybe” to any of these, you need to anonymize!

Common types of personally identifiable data

Information that at first glance seems not-identifiable may become so, especially when combined with other data and subjected to powerful algorithmic analysis. This list gives examples, but is nowhere near comprehensive. Do evaluate for your context.

-

Age

-

Ethnicity

-

Gender

-

District/County

-

Highest Level of Education

-

Medications prescribed

-

Geo-location of login

Thinking about risk

Once you have done your data sensitivity assessment, you need to do a risk assessment of the context. This gives you an idea of how dangerous the data could be for the data subjects if it got out, and how much danger there is for that. Some of the things you should think about are:

-

What might be the consequences be for individuals or groups in the de-identified data if it is reversed?

-

What people or groups may have an interest in trying to re-identify your data? (Intelligence agencies, hackers, curious data scientists etc.)

-

What other data sets are available that may result in re-identifying the data you are releasing?

-

What is your release strategy for your data? (For example, how is it being released to media? Is it possible that they may accidentally/deliberately add identifiable data?)

-

What technical and version control methods are you going to use? (For example, to ensure you release the correct anonymised version of your data)

Anonymisation Techniques

These are some techniques that help in anonymising data, once the process above has yielded that it may be advisable to to do so. For more detailed descriptions of these techniques, their limitations and in which contexts they are most appropriate, see the anonymisation guide produced by the UK Information Commissioner’s Office.

-

Data masking:

This describes supplying only part of a data set (e.g.. taking out columns from a spreadsheet) or deleting these parts from the data set completely.

-

Pseudonimisation:

This describes the exchange of values for codes - this way, for example a name might be replaced with a number, but the same number will show up in every instance where the name was.

-

Aggregation:

Instead of providing the raw data, this would aggregate especially small amounts of information; rounding large numbers, or providing only small samples of larger data sets.

-

Derived data:

This describes a process where the original intent is kept, but the output changed. An example would be to provide the age of a person instead of the exact date of birth.

CASE STUDY: New York Taxis

In 2014, New York City released data under a Freedom of Information Request on 192 million taxi trips and fares made the year before. It held data on items such as pickup and drop off points. This potentially had a lot of useful research benefits, such as city planning. It also contained personally identifiable information about the name of the driver, taxi license and taxi plate number - this information was supposed to be anonymised. However, this anonymisation was very soon worked around, leading to a lot of intimate information being available online, about both drivers and passengers.

While an effort had been made to hide these pieces of information using a method known as “hashing,” it was undermined by a poor understanding of how it works. For example, due to the fact that taxi license numbers are assigned using a specific six or seven digit method, the anonymising method was weakened because it was limited to only three million possible combinations. It then took only minutes using a modern computer to reverse the anonymising method and reveal taxi license numbers. Due to the fact that the NYC Taxi and Limousine commission also provides data linking real names to taxi license numbers, researchers could get to the name of the driver.

The result was that it was possible to figure out who was the driver of nearly every one of the 192 million journeys. From this it was possible to determine how much money each driver made, where they lived, the dates and times when they were working and in what areas they worked. In some cases, it was also possible to infer journeys made by members of the public, in particular celebrities, or visitors of strip clubs.

Sources: On Taxis and Rainbows: Lessons from NYC’s improperly anonymized taxi logs, NYC Taxi Data Blunder Reveals Which Celebs Don’t Tip—And Who Frequents Strip Clubs.

Get Help

It can be helpful during this process to create an expert group of advisors who have experience with your project and with releasing data in a safe manner. Ideally some of these people will be outsiders, with a good knowledge of the areas in which you work but without potentially biased connections to the project. The overall objective of such a pre-release review is to review all possible negative scenarios that might occur because of the data.

Judging by many previous failures, it makes sense to also seek advice from people who have skills relevant to de-anonymising and de-identification, such as data scientists, open data experts and ethical hackers. Pre-release reviews should also include increasing your protection methods in light of the potential increase in attention you may be subject to afterwards. For example, if original data sets are still not secured properly (physically or digitally), now is the time to ensure you do this. After release, you may find it becomes harder to do this, especially if adversaries are technically adept.

Further Resources

-

The UK Anonymisation Network provides consultation and training for NGOs.

-

Anonymisation guide produced by the UK Information Commissioner’s Office.

Presenting data

Power and the visual

There are many ways of presenting data: from infographics to narrative reports, case studies and long form investigative articles, to graffiti or conceptual art. The list goes on, but what’s important is that different media bring different ethical and moral challenges with them when transforming data into message.

No data is neutral, and presenting information can reveal even more biases. Use data as accurately as possible, and take care not to misrepresent topics or skew the data in order to suit your particular advocacy or campaigning need - it will make for an unreliable and easily discreditable campaign, and it will probably put your organisation’s reputation at risk. More importantly, you are breaking the agreement with the people you are representing.

Visual and narrative manipulation and misrepresentation of data, be it by chance or on purpose, is an issue of great importance. Publishing your data is often the last mile, and can be the culmination of the whole project. Digging deep into visual wizardry is outside of the scope of this book; however we warmly suggest reading up on the subject before going public. A very good starting point is Mushon Zer Aviv’s short essay “How to lie with data visualisation”.

Power and representation

In most initiatives dealing with development, vulnerability and marginalisation are critical issues for the people we work with. As with other elements concerning data, inclusion of marginalised people is something we have to be sensitive to. Examples of these groups could include women, persons living with disabilities, LGBTI communities, people from certain geographical areas or people of different racial, ethnic and cultural backgrounds.

When presenting data, ensure that these groups are appropriately treated and they are not being omitted, trivialised, judged or romanticised. Be intentional in how they are represented and what this means for your participants and beyond.

CASE STUDY: “I know where your school is”

A local NGO was involved in investigating and documenting human rights activities. They used the results to pressure their own government. One of their initiatives was to interview people on camera and produce a documentary about the country - seeking to give voice to victims. To protect the participants, they took steps to keep their identities secret and told them their stories would not be traceable to them as individuals. The NGO subsequently put this documentary online to expose the issue and feed into their other advocacy activities. However, they had little experience in editing video and and when they release the footage, faces were blurred but not sufficiently (e.g. when people got up or moved on their seats, their faces would be visible for a few instances) and it had not been considered that victims speaking about what exactly perpetrators had done to them would mean they could be identified even without their name having been stated (since at a minimum, the actual perpetrator could identify their victims when testifying a certain level of detail). They also failed to consider the danger in the footage of easily recognizable location features (such a school signs in the background, or buildings which can be easily found through Google Maps or Earth and lead to identification). In at least one case, an interviewee who had given testimony was re-victimized by subsequently getting detained by government forces and badly beaten.

Lessons:

-

Do not assume that the consent of the person you are documenting also means you do not need to check that they fully understand the risks and potential implications

-

Your staff should make the final decision if it is safe to release or not and they should have been trained and empowered to do so responsibly (Note on not patronising people: it is important to respect people’s agency while minimising risks to them. So it may not be your call to make to prevent someone from telling their story - even if it entails risks - as long as the person fully understands that. It is, however, your responsibility to make sure that when they think they will not be recognisable, they really are not!)

Mitigation:

-

Consider potential risk of the use of information you collect

-

Make sure to consult the people who actually understand the context and what sensitivity means in it

Further Resources:

-

TacticalTech’s Visualising Information for Advocacy guide

-

School of Data’s Visualising Data course

-

Mushon Zer Aviv’s short essay “How to lie with data visualisation”

Project Closure - What Happens to the Data?

Projects end for many reasons. Funding cycles may close. Project goals might be achieved. Even if a project has not ended, the data lifecycle may end during a project, when data no longer needs to be collected and/or referenced in the project.

In all instances, projects that have a data component must address the end of the data lifecycle. Deciding what to do with the data after it has served its purpose is an integral part of the project design process and should be informed by the risk assessment. Usually, this will encompass the following:

-

Mapping where the data is and ensuring it is only in places where it should be

-

When collected data has been be shared (internally or externally), ensure that responsible data procedures are upheld after closing

-

Disposing with (parts of) the data or archiving it, either internally or externally

Where possible, decisions about data sharing, archiving or disposing should be informed or driven by participants depending on project type.

What data do I have and where is it?

Think thoroughly about what types of data live where, in order to plan for proper project closure.

Be sure to consider all the places where data might be collected/stored. Data can live on paper, mobile devices, centralised (cloud-based) databases, distributed databases (Excel/Access/other applications across individual laptops), etc. Think about whether some of your colleagues might have copies of the data or parts of it on a private device, for example a mobile phone. Remember also that anything you have ever emailed may still be on the mail server - who does this belong to?

You may have gone through a data cleaning process to responsibly share and publish your data, but raw data and metadata may still exist on personal laptops or mobile devices.

Tips on hosted data

If you are using third-party applications for data collection or storage, your data is likely hosted by an external provider. It will be important to work with the external provider (before you sign a Service Level Agreement) to plan how data will be archived or disposed of at the end of the data cycle.

If you are using open-source applications, you probably also host the data within your organisation (but you may also be using an external provider). Either way, ensure you know where your data is and that you have a process agreed upon with regards to how to dispose of or archive it.

Data archiving and disposing is not always a simple process. It will be important to plan the time, resources and budget necessary to responsibly protect your data through the end of the lifecycle.

What if I want to keep the data forever?

A good principle developed from the information security community is to only have the data you need for the time when you need it. You may be tempted to keep your data forever just in case you need it someday. However, the technology, data and political landscape is constantly shifting, and you don’t know if it will be possible to use the information to harm someone or some group in the future. If it is important to keep the data forever, you must plan for resources to continually update and support safe data management practices for the data.

Disposing of data

The key to disposing of your information is knowing where your data is in order to delete all of it (see above on ‘what data do I have and where is my data’).

Deleting digital information is more than just clicking “delete”, but it is not hard to do. As a general rule, everything that is on a hard drive needs to be overwritten several times (there are free tools to help you do this). But if your needs are more specific, do not hesitate to reach out to an expert to help you complete the process.