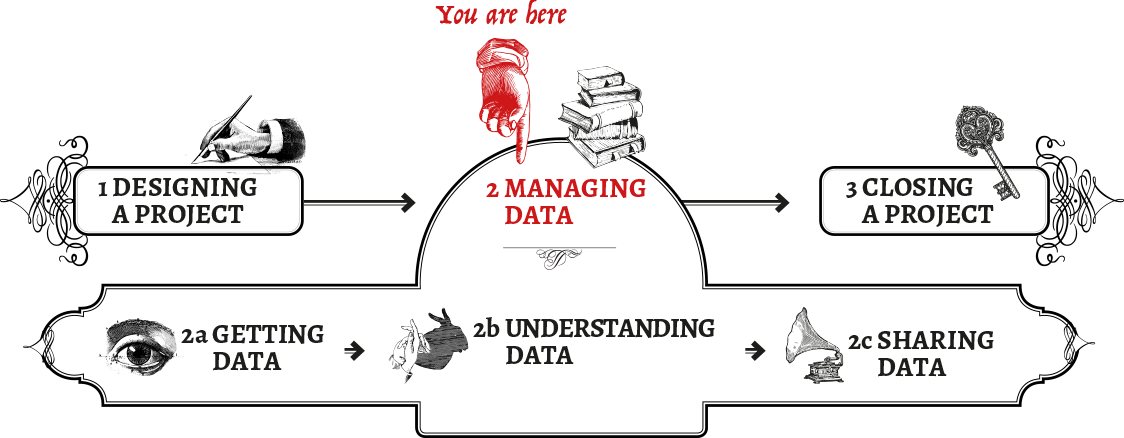

Managing Data

setting up the 'data infrastructure'

A Home For Healthy Data

Give your data a safe space

Data occupies physical space, even if in our imagination the bits and bytes are ephemeral. We store data on hard drives, and these drives have a physical presence, which brings a number of responsibility and privacy implications.

The most obvious issue to address is about data access: who can physically (or digitally) reach that hard drive and copy data from it, or simply take the drive away with them? Another one is location: there are many different places in which we can store our data. It can be on a laptop, on a USB stick, on a remote server in some other country, or even distributed throughout different geographic locations (interestingly, this is probably one of the most common cases). Location issues also bring with them legal implications, especially if we don’t know in which country our data is being stored, and which laws govern digital property there.

This section provides an overview of approaches you can implement to ensure your information is stored, managed and accessed in a responsible, secure and protected manner. To begin with, it’s worth reviewing the general principles of data integrity, and how to manage risks surrounding data storage.

Data integrity

Data integrity is a term used to describe the validity, authenticity and security of information. It includes aspects of both information security and information quality, including how information systems and processes for sharing information are designed. As such, it has some overlap with confidentiality and availability, but is a useful frame of analysis for considering the interaction of technical and human influences on data responsibility.

-

Is the data checked for changes at key points (upload, migration across servers, migration from data collection devices to the main server)?

-

Are changes to the data flagged and are there mechanisms for version control?

-

Are there granular permissions for making changes to the data during analysis?

-

Is the data collection process well-documented? For example, through a codebook or other document that allows newcomers to the project to make sense of the data and understand the relationships between data structure, variables and the data collection process.

-

Does the data include contextual information (potentially in metadata) that is necessary to understand the data?

-

Are data collection notes (eg. on ambiguity, potential duplication, variations, or more contextual information such as notes made during personal interviews) provided together with the data in an accessible format, and the relationship between the two made clear?

-

Are appropriate backup mechanisms in place in case of blackouts or system failures?

-

Is the software used to manage and store the data fully up to date and licensed?

-

Is the data interoperable? Can it be accessed by all the people and platforms that it needs to be? If people who might need to access the data don’t have technical training, is the data available in common file formats (such as csv files)?

-

Have you future-proofed your data by anticipating changes in institutional and contextual factors which could make the data difficult to access or use?

Assessing and managing risks

A thorough discussion of risk assessments is included in the chapter on project design. When planning data storage, there are some specific risks and mitigation strategies that are worth considering.

Some data storage risks and harms:

-

Loss of information (deliberate or accidental)

-

Confiscation of information

-

Data breach

-

Legal threats

-

Malicious attack

Some mitigation strategies:

-

Speak to other organisations in your community who have conducted data projects successfully. Ask them about their storage practices.

-

For bonus points, adapt or use standards for benchmarking your information security procedures, such as ISO 27001 or PCI DSS.

-

Only store the minimal amount of data necessary to complete the task.

-

De-identify data by default (though this approach has its limitations, see the chapter on anonymisation).

-

Encrypt your data at all stages of its collection, usage, transmission and storage.

-

Use secure tools (ideally open source tools which are more transparent) for communication (for a listing of secure tools, see Prism Break)

-

Delete and destroy data safely when it has become insecure.

-

Conduct regular audits and penetration tests of your security measures.

-

Ensure your organisation is capable of managing and updating the system and tools on a long-term basis - as technology becomes outdated and easier to breach

For more information on protecting your information in a physical space, see Tactical Tech’s Security in a Box chapter on this topic

Separate storage for sensitive data

You can store some information separately from the rest. For example, if you have a database with case files, you can replace the names with codes and create a spreadsheet with the codes and their resolution to real names. You can then store this spreadsheet on another, highly-protected computer. This method alone will in most cases not lead to true anonymisation because the case files are easily linkable to real persons.

CASE STUDY: Hacked and then fined!

In 2014, the UK Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) imposed a £200,000 fine on a charity called the British Pregnancy Advisory Service. The organisation’s website had been hacked by an anti-abortion activist who threatened to publish the names, addresses, dates of birth and telephone numbers of women using the service. The ICO determined that considering the sensitivity and risk of the information, the website did not have adequate security and left a vulnerability which could be exploited by the attacker. The organisation also breached the Data Protection Act by keeping data on callers for five years longer than was necessary. Reference: “Abortion service to appeal against £200,000 fine over hacked website”

Further resources

-

For a listing of secure tools, see Prism Break

Dude, where’s my data?

There are many ways to store data that vary in terms of convenience and security. How you store your data should be measured against the particular risks you or your partners may be facing, and your personal priorities: for example, are you more concerned about data loss, or surveillance? These are extremely important questions. Perhaps it isn’t so important to you if authorities have access to your data, but it would be disastrous if the data were somehow destroyed.

Remember: no method of storing data is 100% safe, so it is essential that you backup your data, no matter how or where it is stored.

Data storage

There are a few areas to take into consideration as you make decisions on storage and these could include:

-

Physical location:

Where should data be stored given the type of data and the potential vulnerabilities? Within the country you’re working in, or in another country, and what are the implications of both of these? (eg. differing legal jurisdictions, local internet regulations, especially with regards to storing sensitive data)

-

Digital location:

Should data be stored on‐line or off‐line or both? Or is it open data? (see: The Sharing Spectrum)

-

Ultimate ownership of storage:

Consider pros/cons of third party data storage vs local data storage (e.g. do you have local capacity for local data storage; what is the desired uptime; etc.)

-

Back ups:

What level of data back‐ups are required? (you can never back up too much!) Access: ensure storage method allows for the necessary levels of access. (see: For Your Eyes Only)

-

Data lifecycle:

What is the data lifecycle and who will manage it until the end of the data’s life? (if it ends!)

-

Saving data:

What is the data access / data saving policy, especially for sensitive data (e.g. if data must be downloaded locally it must be encrypted, etc.)

Pros and cons of storage options

Some of the advantages and disadvantages of various approaches may be:

Locally on your PC(s)

Advantages: high security if encrypted, fast and always accessible, easier version control, greater legal clarity over ownership

Disadvantages: lower security if physical theft or confiscation is an issue, poor backup, bad resiliency in terms of physical emergencies - fires or floods for example, poor access except for people located near the machines, potential increase in time spent maintaining the system versus working with a specialist provider.

On your own network

Advantages: increased resilience, easier sharing and collaboration, better backup, greater legal clarity

Disadvantages: increased cost, greater skill needed for effective security, greater reliance on IT support team or third party contractor, potential exposure still to confiscation

Living in the cloud

Advantages: Decreased costs, increased resilience, easier sharing and collaboration, less downtime, better backup, specialist provider knowledge

Disadvantages: Increased legal uncertainty, no control over physical access, nearly impossible to vet people with access to the servers, reliant on cloud company policies which may change

If using cloud hosts, you should ideally identify those who have previous experience in:

-

Providing secure access and protection for your information

-

Supporting the tools which you wish to use

-

Providing good and fast support to their customers - find people who come recommended from trusted members of your network

-

Demonstrable and verifiable commitment to privacy

-

Working with other projects in the humanitarian or human rights field

-

Working within the legal jurisdiction you need

-

Protecting physical data: securing your information from theft, damage and loss

For many people, information security often makes them think only of digital data. However, physical data protection is a vital process, as gaining physical access to data often requires less technical skill than a cyber threat and can often be an easier strategy for a potential adversary.

Imagine if your office or home were burned down or broken into today - what would you wish you had thought of in advance? Some things to think about include the following:

-

Location of data:

The physical security of locations where you store physical data (such as paper) or physical media (such as laptops, USB sticks, DVDs, SD Cards, hard-drives). Are they all in the same location, and easy to find and gain access to?

-

Access to sensitive locations:

Who has access to your office, home and working environment. Especially to areas of highest sensitivity such as server rooms, research desks, consultation rooms, meeting rooms etc. Consider using high-grade locks, CCTV, fences etc.

-

Installing appropriate fire safety controls

-

External staff:

Vetting all staff and contractors such as cleaners or security guards

-

Using an inventory:

Creating and consistently updating an inventory, to enable you to be able to identify any loss or theft of data.

-

Building a security incident registry:

This should be filled out if any member of staff physically sees anything suspicious or has an unusual incident occurring with their IT equipment. It allows for monitoring and identification of incident patterns which may otherwise have been missed. For help in identifying suspicious digital incidents, see Digital First Aid

-

Getting rid of physical waste:

Regularly shredding and disposing of any paper waste

-

Regularly changing security procedures:

For example, changing keys, cards, pin codes or other access control mechanisms, particularly following a change of staff.

Further resources

For your eyes only…?

Who can access the data?

The person ultimately responsible for the data will need to have both physical and digital control over the data. Physical access control means having control over the documents, computers, servers and working areas where data is kept. On the digital side, check that are you doing all you reasonably can to secure your data - for example, using strong passwords, encrypted connections, VPN, logging, two factor authentication etc.

To work out what kinds of permissions and controls others in your team might need, mapping the types of users and what kind of access they will need is a useful exercise to undertake early in project planning.

CASE STUDY: “Human Trojans”

Many NGOs work on areas that involve high stakes and powerful interests, such as when it comes to operations in natural resource issues (oil, diamonds, gas). This often involves collecting information on the ground in countries where those resources are extracted (sourced from governments, companies, local people) and then transferring this information to an international office in another country – often in the Global North – for analysis and reporting. In this case, it was a company that was adversely affected by one of the NGO’s reports that started wondering about the source of leaks that caused negative information about their practices to end up in the NGO reports. It then hired private intelligence services to specifically find ways to get people working at the international offices on their payroll. This time, the attempt to infiltrate the international office to locate the sources was unsuccessful since some of the targeted employee reported it. The assumed intention of the attempt was to locate embarrassing information on the NGO to use as leverage, potentially embarrass their donors, bug their offices and place trojans on their computers.

Lessons:

-

Human beings are the biggest risk

-

Provide access to information on a need-to-know basis only

-

Even if local operations are secure, complacency in international offices may increase vulnerability

Mitigation:

-

Strong vetting of staff is crucial

-

Conduct and continuously update a threat assessment, especially when new data is released

-

Understand your potential adversary

-

Think also about physical access control of offices

Setting permissions

A general security principle is to limit user access to only the minimum amount of data that they need to be able to do their work effectively - and only have access for as long as they need it. This ensures the privacy of people who have had their data stored by your organisation, and also reduces the potential impact of security incidents such as a data breach or data loss. Put otherwise: if only very few people have access to the whole database, then there is less chance of them accidentally deleting all of it.

People should also only have the minimum permissions that they need to do their job. To do this, you must identify the broad categories of users and what information they will need to work with. For example, a role such as a remote medical clinic worker on a short term project might only need to access data relevant to the area they are travelling in for a few weeks of their deployment. This means they only need to have access to office files and IT systems which are relevant to that specific area. However, someone working as a country researcher tasked with identifying trends across the country might need access permissions to all of the data in the country for a longer period. Although it might be less work for you to simply give out the widest possible permissions to people, to avoid them having to come back to you and have them adjusted. The easy route is not always the most sensible, and doing so could create a lot more work for you in the future.

Access permission also includes items like auditing and controlling who can manipulate, manage and delete data. The person with responsibility for managing and creating access should schedule regular times to audit the users types and remove people who no longer need access - for example, temporary workers such as contractors and interns. Unfortunately this is particularly important for potentially disgruntled staff such as workers who are fired - a number of examples exist of people using their old job credentials to illegally access data at their previous roles.

HUMAN RESOURCES: Bear in mind that if you are introducing people to a new set of tools or methods for accessing the data, they will likely require ongoing training sessions and follow up.

CASE STUDY: “Donor Data Danger”

In a project involving sensitive human rights work, two of the donors involved insisted collecting a huge amount of data on operations, including names of people involved and receipts for all activities. Within three months of the project, however, both of those donors discovered inside threats. In each case, some of their employees had become disgruntled with their working conditions and subsequently left the organisations, taking with them a large amount of data – not only on one project, but all the NGOs and individuals the donor had been working with and/or had funded. In some instances, this information was even channelled to the country’s intelligence services directly or indirectly, exposing a large number of people to high risk (including employees, sources, beneficiaries, as well as their connections and networks). At the high point of this crisis, even the regional director of one of those donors said we should stop passing sensitive information to his employees, as he couldn’t trust those in the organisation. While it is impossible to prove causality, a considerable increase in attacks and disruption of those NGOs’ work that had linkages with those particular donors was reported.

Lessons:

-

Be aware and prepared to actively disagree with your stakeholders, even if they are your funders

-

International actors can be just as much a threat as anybody else – secure your info from the bottom up, but also all the way up

-

Don’t think because an organisation has an international reputation, they are automatically responsible data holders – in the end, you will be responsible for your data and the people it reflects!

-

Encourage a culture of responsible access controls and permissions, not just within your organisation, but also in organisations you share your data with.

Collaboration

Controlling access effectively means selecting the right choice of methods and tools which balance the need to keep information secure, and also allowing effective collaboration in the field. A number of things which need to be considered in this area include:

-

Types of data:

What are people collecting, and where are they putting it?

-

Tool choice:

Suitability, usability, support, updates, cost, local vs network, network vs online access, mobile vs desktop, open source vs proprietary.

-

Levels of verification for the data:

How many people should be looking at and checking the data?

-

Speed of internet connections for users accessing data:

eg. if users are collecting data on their mobile devices in the field, the mechanism chosen for collaboration will need to be able to cope with receiving from such devices. Depending on phone signal, this may mean collecting and sending video from remote locations is not possible. This should be thought about prior to committing to any technical infrastructure.

-

Access points:

Collaboration often requires remote access which can occasionally decrease security, as it opens up a number of less easily secured access points to a network. As such, tools and methods such as forcing regular password changes, two factor authentication, network logging, VPN only access, etc. are important to help mitigate such risks. (see: Security Resources)

-

Layered access:

Having appropriate access permissions is pivotal to ensuring that strategies for separating information will work. Note that it can also be an option to only allow access when several people co-sign, that is, certain data is only accessible when more than one person unlocks it.

But don’t overdo it!

It’s important to make sure that there are rigorous controls on how data is accessed, but you don’t want to lock it up so tight that you are unable to access the data when needed. In fact, projects should take active steps to make sure that the data can be accessed by the right people at the right times. Below are some concrete steps to take that will ensure data integrity, while also making sure that it’s available only for the right people at the right time.

-

Backing up your data: regularly back up your files, and test these procedures on a regular basis.

-

Building redundant systems in case of failure: For example, it can happen that hard drives or essential equipment can completely fail without warning. Without redundancy like alternate data servers, this can completely disrupt your operations.

-

Building architecture with extra capacity: data collection can be disrupted when space runs out on storage or collection platforms. You should try to ensure any system you have can be easily and cheaply expansible.

-

Emergency situations: unexpected interruptions like natural disasters or internet shut downs can interrupt data collection and transmission. Having a plan for such occurrences (for example, to shift to satellite links) can minimize the damage such interruptions may cause.

-

Targeted disruption: sometimes someone, or something, may target your data specifically. Ideally, threats such as this will be identified in a risk assessment, allowing you to build extra capacity into your architecture to deal with such problems. If hosting on your own, fighting against malicious attacks (such as Deliberate Denial of Service) can be very expensive. However, services exist which specialise in absorbing such attacks and using these is recommended best practice - such as Deflect and the commercial provider Cloudflare.

Legal Considerations

All steps of the data lifecycle are subject to legal requirements, and managing data securely requires understanding and meeting these requirements adequately. It’s better to be proactively aware of the legal restrictions on your work, than to realise after the fact that you’ve been breaking the law and face monetary fines as a consequence, or that you can’t legally do what you were planning to do. With the growth of cheap cloud computing (ie. data stored on servers not owned by your organisation), it is often difficult to know exactly where your digital data is being held. Popular providers of email and storage such as Google, Amazon, Facebook, Yahoo, DropBox, GitHub make use of infrastructure spread across a number of international sites. For example, Google stores data in the US, Ireland, Belgium, Finland, Chile, Taiwan and Singapore; so, which country’s laws affect your data? It’s not always easy, but you need to understand the legal ramifications of where you store your data.

What types of laws and procedures apply to your data project?

Jurisdiction

It can be challenging to understand how management of your data is affected by the laws of the countries in which the data is stored. Some common grounds for jurisdiction include:

-

The countries where your organization is registered

-

The countries where your organization operates

-

The countries where your data is stored (for cloud storage, this can quickly become complicated and involve multiple countries)

-

The countries where your users, participants or subjects are

Sometimes the terms of service or specific policies will determine which law applies, but often not, and other jurisdictional claims can supercede these. As a point of departure, it’s worth assuming that all of these jurisdictions apply. Talk to your technical and legal team to determine which don’t.

Data protection laws

A number of countries have strong data protection laws which place limits on the types of data which may be collected from individuals. They also often include specific legal requirements about the methods used to store such data, along with mandatory reporting and monetary fines for breaches. Individuals about whom data is stored are often granted a number of rights, such as access to their information and the right to have their data correction and/or removed.

For an overview of data protection laws in different countries, you can browse here and here.

It might require some careful thinking, but granting people rights to access data in which they are reflected is crucial, especially for organisations which collect sensitive data, such as witnesses of human rights violations and perpetrators.

CASE STUDY: Data protection laws

Organization X was a human rights organisation in sub-Saharan Africa collecting and publishing data about human rights abuses by the local government. The government was embarrassed by this and wanted to stop the organisation from functioning effectively. Rather than attack the organisation physically, which they knew would draw international attention, they decided to disrupt its work by tying them up in nefarious legal cases. For example, the organsation was severely punished for poorly protecting data, minor health and safety violations, and accounting malpractices. While the cases were all eventually thrown out, this caused harmful disruptions to the organisation’s work and caused them to spend their limited resources on lawyers’ fees. Adhering to relevant data protection laws may not prevent this kind of legal tactic to be used against you, especially if the law-makers are targeting you specifically, but it may limit their techniques.

Encryption technology laws

Local laws in a number of countries (such as Sudan, Yemen and Pakistan) place limits upon the nature of encryption software allowed for the communication and storage of data. System architecture and tool choice must incorporate these concerns. Other laws which affect the use of encryption include:

-

mandatory handing over of encrypted data if requested by government authorities

-

mandatory metadata collection by specific industries, eg. telecommunications (and potentially their subsequent sharing with government authorities)

-

laws requiring the weakening of encryption software, such as programmes for export: some countries (eg. Pakistan) won’t allow the use of programmes which contain certain levels of encryption. Other countries (like the US) try to control the distribution of programmes with high-strength cryptographic controls - this originated from countries not wanting to share their

-

high-strength cryptographic software with potential adversaries.

-

those which require individuals to disclose their passwords (such as the UK) upon government request. NGO registration laws

An increasing trend in many countries has been the introduction of strong laws which regulate the presence, funding and/or activities of NGOs in their countries (for example, Russia, Ethiopia, Egypt, Hungary, Kenya and South Sudan). Projects initiated in the country must consider these when building data management infrastructure, and when thinking about different country presences.

Jurisdictional issues

Organisations should be aware of laws that would give governments access to information stored on servers hosted in their countries. For example, Boston College was forced to give interview information (tapes) to the Police Service of Northern Ireland after they were subpoenaed. Citation

It is very difficult to protect digital information from subpoenas (for example, see this map on US extradition treaties) so it is important to adhere to a minimalist approach to collecting or storing sensitive digital data (or don’t store it all). See section on Getting Data.

Organisations must also be aware of cross-jurisdictional issues in relation to their data management. It is not unusual for data to be collected in a country office, transferred to a regional office in another country, then onwards to the organisation’s headquarters in a third country. Also, some states or regional groups place strict conditions on where their citizens’ data may be transferred to - for example, the EU/US Safe Harbour law.

Copyright and Patent

Copyright and patent issues related to the collection, storage and dissemination of your data are important laws to consider. Ensuring you have the correct licensing for your projects and infrastructure can help reduce unexpected restrictions and costs further into your project. Open licensing such as Creative Commons options, and open source code such as MIT or BSD licenses provide tested and off-the-shelf solutions for your data, and open the door to your peers being able to verify your data, or mixing it with other datasets that you might not have collected yourself, but which would strengthen your project. (See section: Disseminating Data for more information on licensing and advantages of open licensing)

Procedures on presentation of evidence

If you intend on using your data in legal cases, you should understand the requirements used in court for the presenting of evidence. Approaches to digital data differ significantly in each jurisdiction. However, some standard basic requirements are that data management systems:

-

Allow for an auditable chain of custody (ie. make it possible to know who has had access to the data at all times)

-

Ensure the integrity and authenticity of the data. For example, a number of technical processes (such as hashing and forensic examination) allow a comparison between original and other versions. Authenticity can be enhanced through the collection of extra information such as metadata. However this must be balanced against the extra risk this may pose to collectors - as often it is not clearly understood by the people involved.

-

Ensure that data is verifiable. The data content itself in many cases should be verifiable. For example, the massive growth of online video posted to sites such as Youtube, Vimeo and LiveLeak has driven the development of methodologies to verify what is shown in the footage - is it showing what it says it is showing?